This book is always right next to me when I am working. Every time I see it I am reminded of how it changed my life. It still blows me away.

It was about 24 years ago. My then six-year-old daughter and I were at a garage sale on the island of Kauai. I remember her coming up beside me, tugging on my arm, and holding up this book. She looked at me and said, “Do you think this book would be good for helping me read better Daddy”.

My first reaction to the book was utter surprise. I was reasonably aware of Steinbeck. I used to love hanging out in Cannery Row. But I had never heard of Steinbeck writing a King Arthur story. It wasn’t something that would be good for her to read, but possibly something I could read to her. I opened the book and began reading its introduction. These were Steinbeck’s very first words:

“Some people there are who,

being grown, forget the horrible

task of learning to read. It is

perhaps the greatest single effort

that the human undertakes, and

he must do it as a child.”

For reasons I will explain shortly his opening words floored me. I continued. These were the very next words:

“An adult is rarely successful in the undertaking – the reduction of experience to a set of symbols. For a thousand thousand years these humans have existed and they have only learned this trick – this magic – in the final ten thousand of the thousand thousand.

I do not know how usual my experience is, but I have seen in my children the appalled agony of trying to learn to read. They, at least, have my experience.

I remember that words – written or printed – were devils, and books, because they gave me pain, were my enemies.“

I remember thinking to myself, how could a Nobel Prize winner for writing have ever thought of written words as “devils” and “enemies” or as the cause of “appalled agony”? I kept reading the introduction. Steinbeck went on:

“Some literature was in the air around me. The Bible I absorbed through my skin. My uncles exuded Shakespeare, and Pilgrim’s Progress was mixed with my mother’s milk. But these things came into my ears. They were sounds, rhythms, figures. Books were printed demons – the tongs and thumbscrews of outrageous persecution. And then one day, an aunt gave me a book and fatuously ignored my resentment. I stared at the black print with hatred, and then, gradually, the pages opened and let me in. The magic happened. The Bible and Shakespeare and Pilgrim’s Progress belonged to everyone. But this was mine. It was a cut version of the Caxton Morte d’ Arthur of Thomas Mallory.”

I had chills. He was describing the vast gulf between learning by listening to words and learning to read written words. He was describing a kind of Helen Keller moment when learning a code suddenly opens up a new universe. He was calling written words (not oral ones), the “tongs and thumbscrews of outrageous persecution“.

Steinbeck went on to share that the reason the book “clicked” was its orthography:

“I loved the old spelling of words.“

“The very strangeness of the language dyd me enchante, and vaulted me into an ancient scene.”

“Perhaps a passionate love for the English Language opened to me from this one book.”

As I continued reading the introduction, I learned that it was this book’s old English spelling (like Helen Keller’s “water” code moment) that clicked with his mind and launched Steinbeck’s life as a reader and writer. Finally writing made sense to him and it opened him to all he became as a master of English. In the later stages of his life, when reminded of the “horrible task of reading” by his own children, he wrote this story, partly to honor the story that changed his life, and partly to leave for other kids a modern adaptation of the great story of King Arthur.

Encountering the introduction to that book changed my life. Here was a giant of literature writing back in the 1960s and pointing to both the cause and effects of this most uniquely confusing challenge.

A big part of the reason the book hit me so hard was because, at the time, I was deeply worried about what I saw happening to my little girl as she struggled with reading. She was so beautifully bright and alive, but she was starting to wither into a spirit-darkening downward spiral of shame. Because she thought she wasn’t “good enough” at learning to read, she felt shame in relation to everything related to reading.

That she would be the one to bring me this particular book felt like a “sign”.

It had been a decade since my son had provided a similar thumping. His kindergarten teacher once described him as having the vocabulary of a 20-year-old. We had never tried to explicitly teach him to read, but he had picked up a lot of sight words from games. He was great at learning how to play video and computer games. One of the things that he learned early, that made him so good at learning these games, was that he could trust them. He knew he would get stuck and that anytime he was stuck the challenge was to learn his way forward. Games worked that way. They were full of little challenges that would stop him, but there was always something he could learn to get going again. He had come to trust that though he could be stopped by something in a game that didn’t make sense to him, it would make sense once he learned what it was.

I will never forget, like the Steinbeck event, the day he came home from Kindergarten and marched into my office with his book in his hands. With a stunned look on his face, he opened the book, and turning to a page pointed to a word and said, with the tone of someone appalled and in disbelief, “Dad, it can’t be like this!”

“What do you mean?” I asked.

He said: “There is no way those letters make the sounds in that word!“.

For the first time in my life, despite being a student of learning, I encountered the confusion of English orthography. Here was my verbally dexterous intelligent boy – someone who had confidence in his ability to learn – someone who trusted in the learnability of things – pointing out just how crazy stupid and bizarre our orthography is to a bright young mind.

After he drew attention to it, I devised a way to help him take off in reading that worked so well that he was off to full-speed self-improving reading within a couple of weeks. But the whole experience inspired me to begin developing a new kind of “orthography overlay” – a way of varying the visual appearance of letters in ways that would make it easy to recognize which of a letter’s possible sounds it is making when you see it in a word. It wouldn’t change the alphabet or spelling, it would use a small number of letter font styles to cue readers through the letter-sound confusions that make learning to read so hard.

Back in 1991, I sent an outline of the idea to nearly 1000 educators. I called the font tech “P-Cues” (short for phonics/pronunciation/parallel/processing cues) and the overall approach “Training Wheels for Literacy”.

“P-Cues certainly looks good to me”. Marvin Minsky – Director of MIT’s Media Lab and Founder of its AI Lab

“As a linguist I’m all in favor of your method”. Martin Haspelmath Max-Planck Institute fur evolutionare Anthropologie (Germany)

“The Training Wheels approach is a novel and promising way of tackling a long-standing serious social problem, the functional illiteracy of many young people in the United States and other English-speaking countries.” Robin Allott – Linguist, Author of the Motor Theory of Language Origin 1989 and of The Great Mosaic Eye 2001 (on the origin and usefulness of the alphabet). (England)

I had some greatly encouraging responses from scientists and thought leaders, but every educator I sent it to either ignored it or thought I was from Mars. Those responses from educators were my first taste of the encrusted thinking, oversimplifications, warring beliefs, and risk aversions that characterize the “reading wars”. Having no idea how to break through the noise, I let Training Wheels fade into the background.

Then, years later after my daughter was diagnosed with an auditory memory processing deficit, and I felt her struggling with reading, the urgency of the concepts came rushing back. She had the same appalled disbelief that words could be written so irrationally confusing that my son did, but her auditory memory issue made her struggles far worse. She could strain to work out a word and then encounter the same word again a sentence or two later and have to go through the struggle all over again.

Inspired by her struggles, by the time of the garage sale encounter with Steinbeck, I had made a lot of progress toward developing “Training Wheels for Literacy“. But when my daughter brought me that book, I realized something that changed my life. I realized that the reason we have so many children being so seriously harmed by what my daughter was feeling and Steinbeck described as the “appalled agony of trying to learn to read” was that most parents and educators have no idea what’s so challenging about learning to read. Steinbeck had nailed it except that it wasn’t just that “some people there are“, but most. That’s when I decided to shift my focus to producing what would become the 130+ video segment documentary “Children of the Code“.

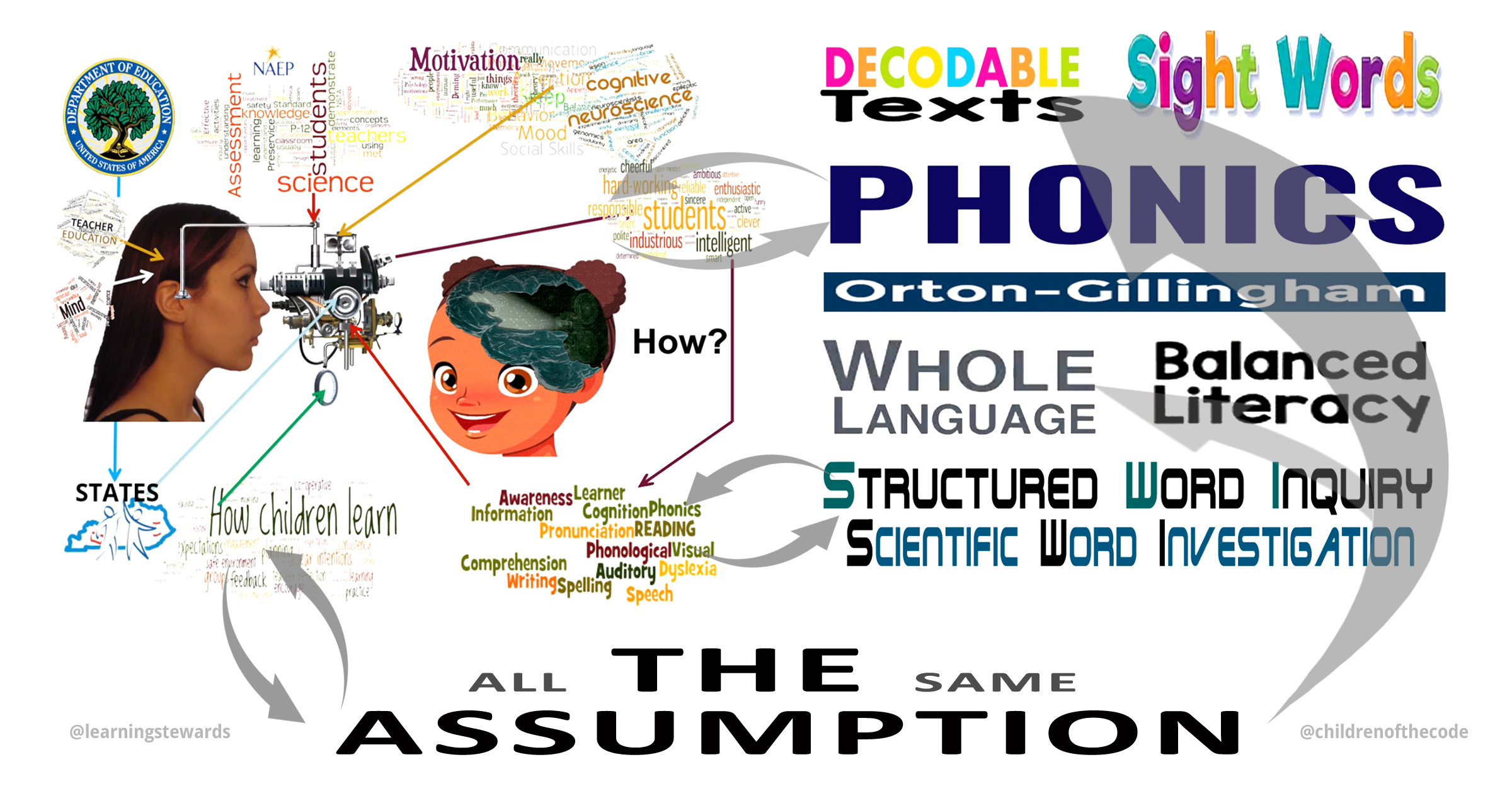

Children of the Code didn’t offer or advocate any solutions. Instead, the documentary and the hundreds of workshops and talks it spawned, focused on the challenges involved in learning to read:

The central purpose of the Children of the Code Project is to help educators, parents, and all who care about children, develop a deeper first-person understanding of ‘what is at stake’ and ‘what is involved’ in learning to read. The better educators and parents understand the challenges involved in learning to read, the better they can help children learn through those challenges.

Today, it’s nearly 23 years later. What still stuns me today after over a thousand hours of interviews with the scientists and scholars behind the “Science of Reading” and thousands more hours in deep-dive dialogue with other thought-leaders in related fields, is that nothing has changed. Though a modern editor might change the words a bit, Steinbeck’s point remains as valid as ever.

“Some people there are who,

being grown, forget the horrible

task of learning to read. It is

perhaps the greatest single effort

that the human undertakes, and

s/he must do it as a child.”

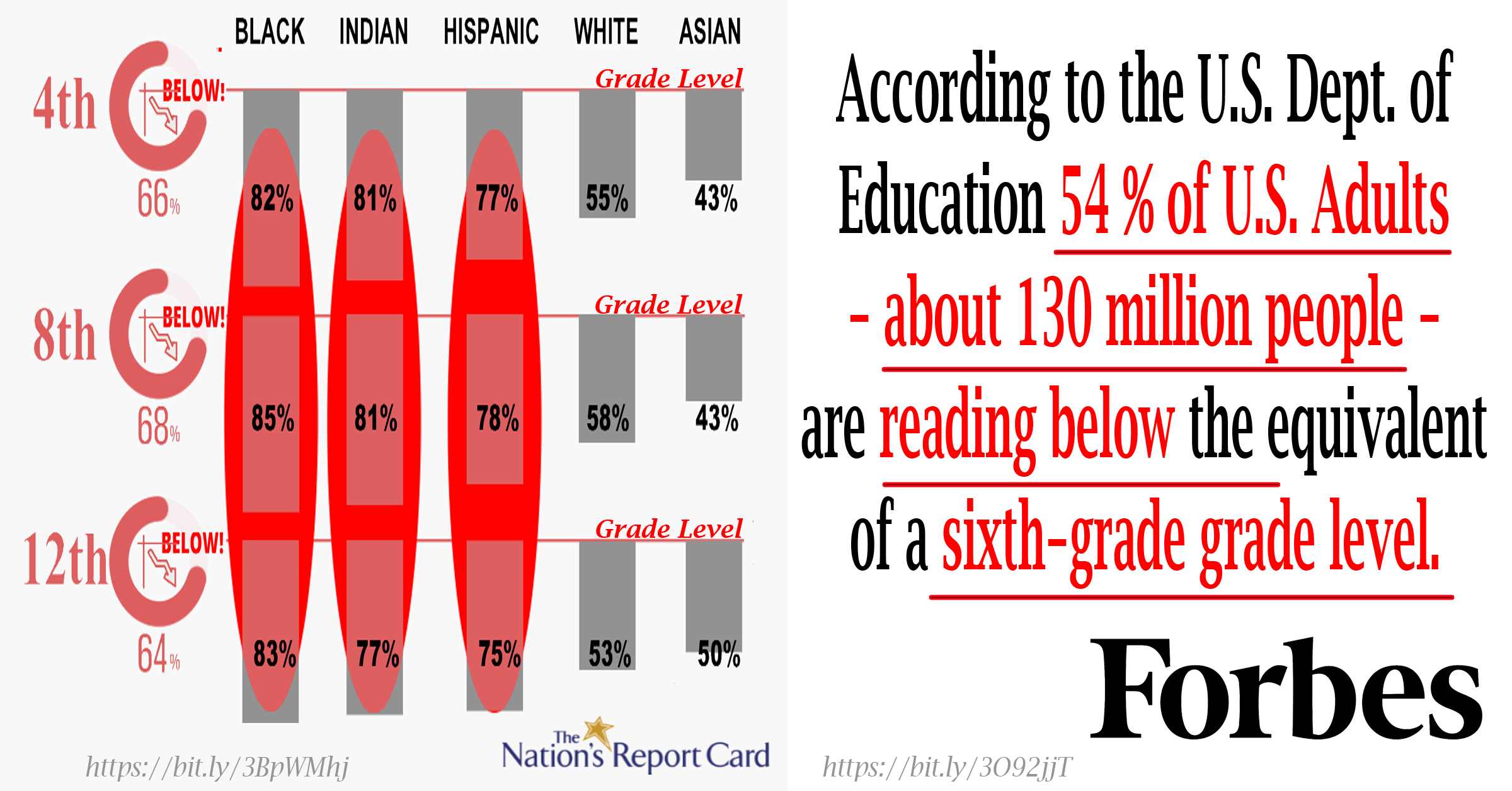

I think the deeper problem is that most people think they do understand what’s involved in the effort. It’s the “paradigm inertia” that disables our learning and by extension our children’s. Today’s national reading scores are just about the same as they were three decades ago (when we began recording what is now NAEP data).

After “Children of the Code” I continued working on “Training Wheels for Literacy” and “P-Cues”. Today they have been incorporated into and in some sense superseded by the “Online Learning Support Net“.

As for my daughter, she went on to read well, graduated college as “neuroscientist student of the year”, and she remains an inspiration!

| Most Adults and Kids Less Than Proficient |  |

| Learning to Read |  |

| Flawed Assumptions |  |

| Literacy Learning: The Fulcrum of Civil Rights |

|

| Challenging the Experts |  |

| Reading Shame |  |

[…] Steinbeck’s Appalled Agony […]

[…] Steinbeck’s Appalled Agony […]

[…] Steinbeck’s Appalled Agony […]

[…] correct information” (wow). Ironically, it was his daughter’s experience of harassment (something I can relate to) that woke him to the dangers of misinformation (I wonder if his daughter was influenced by […]

[…] Steinbeck’s Appalled Agony […]